I’m not really into top-down approaches. I believe that in most effective systems, decisions happen at the individual level.

For instance, take the case of ants or bees, while there’s structure, there isn’t constant centralized control. Individuals act based on local information, and coordination emerges naturally without waiting for hierarchical alignment.

John Nash described a similar idea through the Nash Equilibrium. It explains how groups can reach a stable state when individuals make the best decisions for themselves while accounting for the actions of others.

Everyone acts in their own interest, but not in isolation. When incentives are aligned, this leads to a balanced system where no one can improve their outcome alone.

The takeaway is that strong systems don’t always need control from the top, they need the right conditions for individuals to make good decisions together.

This idea immediately took over me when I read this recent research – Architectural swarms for responsive façades and creative expression. It’s a collaborative effort by scientists from Princeton University and Northwestern University.

The group aimed towards creating a swarm of robots that makes buildings behave like living organisms. Yeah, you read that right, living buildings. Well, sort of!

From Sun-Tracking Buildings to Swarms That Think

The Al Bahr Towers in Abu Dhabi is an interesting architecture having these intricate geometric panels that open and close like mechanical flowers following the sun.

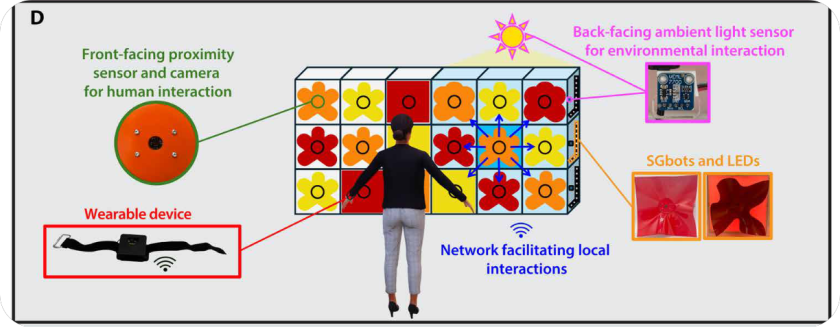

Extending this idea of distributed, light-responsive elements beyond architecture and into robotics, researchers at Princeton University and Northwestern University have created the Swarm Garden, a system of autonomous robotic modules that collectively respond to light and human presence.

The Swarm Garden consists of SGbots, which are 40 autonomous robotic modules. Each one capable of sensing light, communicating with its neighbors, and blooming like a flower in response to sunlight or human interaction.

Now imagine them working together, not through centralized control, but through swarm intelligence, the same kind of collective decision-making that allows bees to build hives and ants to construct bridges out of their own bodies.

This is a level up in smart design, architecture that thinks, or at least gives a damn good impression of thinking.

I Love Systems That Don’t Ask for Permission

I’ve always been a bit obsessed with emergent systems, derived from biomimicry and fractals. Those beautiful phenomena where simple rules at the individual level create complex, unpredictable patterns at scale. Maybe it’s because I grew up watching too much Star Trek and reading too much Isaac Asimov. Or maybe it’s because I’ve seen how much delay happens when everything requires five layers of approval before anyone can make a decision in orgs where the system works in top down hierarchies.

In contrast, emergent systems are almost rebellious in their elegance as they thrive on:

- autonomy

- local interactions

- feedback loops

- adaptability rather than rigid command structures

A flock of birds, a school of fish, a bee hive, a thriving forest ecosystem, all of them demonstrate that complexity doesn’t need to be forced, it arises naturally when each part knows its simple role.

Each ant follows simple rules, follows the pheromone trail, avoids obstacles, returns food to the nest, but together they create highways, and architecture that rivals anything we’ve built. I can’t help but wonder how much creativity and innovation we lose when human systems ignore these principles.

That’s Nash Equilibrium in action, right there in the natural world. Each individual optimizing for itself while accounting for the collective. No boardroom meetings or any two-hour Zoom calls to align on strategy. Just local decisions, and emergent intelligence.

The Swarm Garden is trying to bring that same philosophy into space, let’s see how.

How Does an SGbot Decide What to Do?

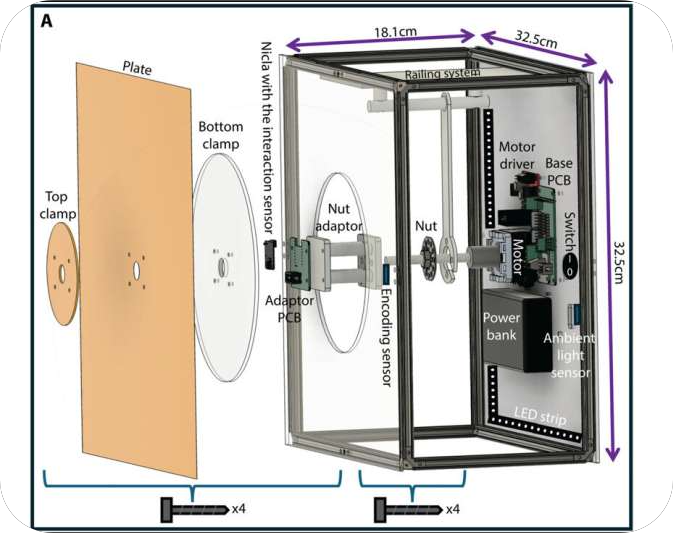

Every SGbot is like a 32-centimeter square panel with a thin plastic sheet stretched across it. Inside is a simple mechanism, a threaded rod that can pull the sheet through a circular opening, causing it to buckle and bloom into these gorgeous flower-like patterns. It takes about 10 seconds to go from flat to fully bloomed.

But the moat isn’t in the mechanical blooming, it’s in what each robot knows and how it decides.

Each SGbot has:

- An ambient light sensor on the back (facing the window) that measures sunlight intensity

- A proximity sensor on the front that detects human interaction

- An encoder that tracks exactly how far the plate has extended

- WiFi connectivity to talk to its neighbors

- LED strips that can change colors for visual expression

The researchers developed what they call the SG_od model, a mathematical framework based on opinion dynamics. Instead of a central computer telling each robot what to do, each SGbot makes its own decisions based on three inputs:

- What its own sensors are telling it (Is the sun blinding me right now?)

- What its neighboring robots are experiencing (Are you guys getting blasted with light too?)

- What the desired room conditions should be (Humans generally like around 750 lux of illumination)

Each factor gets a weight, and those weights adjust dynamically based on conditions. If the room’s light level is already perfect, the system basically says, “Cool, we’re good”, and maintains the status quo. If it’s too bright or too dark, the robots spring into action, each making its own calculations but staying aware of what its neighbors are doing.

It’s Nash Equilibrium for buildings. Each robot optimizing its own behavior while factoring in the collective good.

The Office Window Experiment

The Princeton team actually deployed 16 SGbots on a real office window for 8 days, running continuously for 7 hours each day during August, when the sun hits that particular window hard in the morning and then disappears around 11 a.m. behind a neighboring building.

The goal was to keep the room comfortable by blocking harsh sunlight when it’s intense and allowing more light through when it’s dim.

What happened was beautiful.

The robots responded proportionally to sunlight throughout the day, extending to block harsh morning rays and gradually retracting as the room darkened. The correlation between their blooming levels and the actual light conditions was 0.98 on sunny days and 0.95 on cloudy days. That’s remarkably tight coordination for a decentralized system.

Interestingly, the team then started breaking things on purpose.

For instance, they killed communication between robots by disabling individual sensors. They cut off the room’s ambient light detector.

Surprisingly, it didn’t really fail. It adapted.

When a robot lost communication with its neighbors, it relied more heavily on its own sensor. When a robot’s sensor died, its neighbors picked up the slack and shared their information. When the room sensor went offline, the swarm adjusted its decision-making weights and kept functioning.

The correlation between normal operation and these failure scenarios stayed above 0.83, even on rainy days. For a complex system with 16 independent decision-makers, that’s incredible resilience.

This is exactly what happens in ant colonies when you remove a few workers. The colony doesn’t collapse, it reorganizes and continues building. The system is robust because it’s decentralized.

Systems Work Better When Control Steps Back

I’ll admit, this kind of thinking didn’t come naturally to me.

Earlier in my career, I worked on projects where we tried to anticipate every scenario and control every variable. It was exhausting and, frankly, it rarely worked as planned. The more we tried to centralize decision-making, the slower we moved.

I remember this one project, where we created dossiers, a control system for managing workflow across teams. It required approval at multiple levels for even minor decisions. The theory was that centralized oversight would ensure quality and consistency.

And when it gets into practice, we observed that people spent more time waiting for approvals than doing actual work. Tasks moved from dossier to dossier, sitting in queues while each approval was processed.

And when unexpected situations arose, which they always did, the system couldn’t adapt fast enough because all decisions had to flow up the hierarchy and back down.

It was the opposite of swarm intelligence. It was swarm stupidity.

That experience changed how I think about systems design. I started paying attention to how decentralized networks actually function in nature and in successful human organizations. I read about stigmergy, the way termites coordinate construction by responding to what other termites have already built, not by following a blueprint. I looked at how open-source software development happens through distributed collaboration.

The pattern was clear, adaptive systems give autonomy to individual agents while providing mechanisms for coordination and feedback.

The Swarm Garden embodies this philosophy so perfectly it almost feels like the researchers were reading my mind.

Now Imagine This at Architectural Scale

The real-world window experiment was impressive, but what really makes my imagination run wild is what the researchers did in simulation.

They modeled a massive atrium, 20 meters deep, 20 meters wide, 15 meters tall, and covered the skylight with a 19-by-19 grid of SGbots. That’s 361 units, each scaled up to about a meter across. They ran simulations using actual weather data from New Jersey on the summer solstice.

The results showed something I find genuinely exciting, with enough robots working together, you can create selective illumination. Different areas of the same room could maintain different light levels, all dynamically adjusting throughout the day.

Imagine a library where reading areas stay bright at 3000 lux while study carrels dim to 500 lux for focused work. Or an open-plan office where collaborative spaces have energizing bright light while individual workstations have softer, more focused illumination. And all of it shifts throughout the day as the sun moves, without anyone touching a single control.

No central management system deciding what’s best for everyone. Just hundreds of individual units, each making local decisions based on local conditions and collective goals.

The contrast ratios they achieved were significant, from under 100 lux to over 3000 lux in the same space. That’s real adaptability.

This is where my sci-fi brain starts running wild. Because once you have this kind of distributed, adaptive system at architectural scale, you start wondering, what else could it do?

When Humans and Systems Improvise Together

Here’s where the story takes a turn I genuinely didn’t expect.

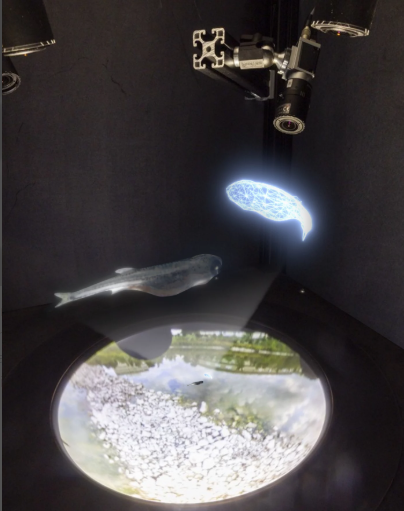

The Princeton team didn’t just want to build a better window shade. They wanted to explore whether these architectural swarms could be a medium for creative expression. So they hosted a public exhibition with 36 SGbots and invited people to interact with them.

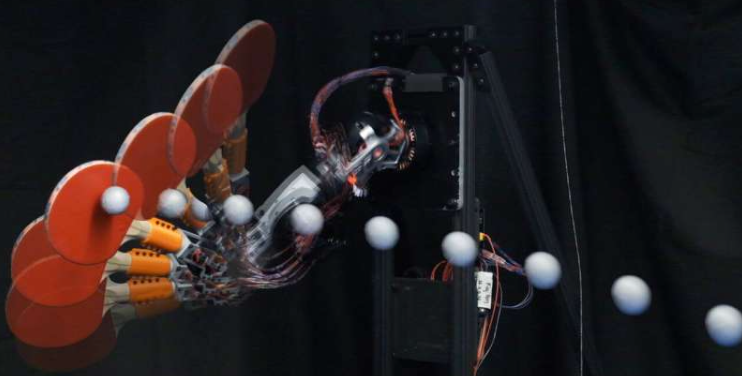

But the experiment that really grabbed me was the dance performance.

They created a wearable device, basically a smart bracelet with an accelerometer, and gave it to Azariah Jones, a professional dancer with 19 years of experience.

As she moved, her arm gestures triggered responses in the swarm. A movement along one axis would propagate a color through the entire system. Another direction would select a random robot and spread a different color outward from that point.

What fascinates me about this is that the system included both predictable and emergent responses. Some movements always did the same thing, turn all LEDs green, for example. But others triggered random selection of robots, meaning the same choreography would create different visual results each time.

So what does it mean?

The dancer wasn’t programming the system or commanding it. She was collaborating with it. Each making decisions, her based on artistic intuition and the swarm’s response, the robots based on sensor input and programmed rules, and together creating something neither could achieve alone.

That’s not top-down control. That’s not even bottom-up emergence. It’s something in between, a dynamic equilibrium between human intention and machine intelligence.

It reminded me of jazz improvisation, where musicians listen to each other and respond in real-time, creating coherent music without predetermined arrangements.

Two Big Questions About This Technology

Okay, so I’m excited about this technology. But there are a few questions that need to be discussed at the right time.

1) The Privacy Thing

These robots have sensors, they track light, motion, proximity. Scale this up, add machine learning (which feels inevitable), and suddenly your building knows exactly where you are at all times, what your daily patterns are, when you leave and return, potentially even who you’re with based on movement patterns.

The researchers were upfront about shared data in the exhibition mode. But what about in:

- personal deployments

- office buildings

Who owns that data? Landlord, employer or some third-party analytics company that promises to “optimize your experience”

We’ve already seen how smart home devices become surveillance devices.

- Amazon Ring doorbells sharing footage with police.

- Smart speakers recording conversations.

- Fitness trackers revealing military base locations.

Now imagine your walls are watching and optimizing, ostensibly for your benefit, but with all the attendant risks of data collection and potential misuse.

I don’t think the solution is to not build this technology. But we need to be asking these questions now, at the proof-of-concept stage, not after it’s deployed everywhere and we’re trying to retrofit privacy protections.

2) The Energy Question

Each blooming cycle is relatively slow, about 10 seconds, partially because faster movement requires significantly more power. Scale this to thousands of units on a massive building, all blooming and flattening throughout the day, and you’re looking at serious energy consumption.

The researchers acknowledge this. They mention exploring kirigami-inspired cuts in the sheets to reduce actuation power, and investigating more efficient mechanisms. But let’s be real, this is a hard problem.

Every piece of smart building technology I’ve researched promises energy savings through optimization, but the devices themselves consume power. Sometimes the optimization savings outweigh the operational costs. Sometimes they don’t.

I’d love to see a full lifecycle analysis. What’s the total energy cost of manufacturing, installing, operating, and eventually disposing of these systems? How does that compare to the energy saved through better daylight management and reduced HVAC loads from smart shading?

They’re essential engineering questions that determine whether this technology actually contributes to sustainability or just looks cool while consuming resources.

Now comes my science fiction mind, what if different Swarm Garden installations could communicate with each other?

Imagine walking through a city where buildings share environmental data, creating a distributed sensor network that responds to weather patterns, air quality, even crowd dynamics at an urban scale.

Building A detects rising temperatures and incoming storm clouds, and shares that information with Building B three blocks away, which pre-emptively adjusts its shading in anticipation.

That starts to sound like a science fiction movie, where environments that aren’t just responsive but anticipatory, learning and adapting to patterns we might not even consciously notice.

Except instead of top-down algorithmic control, it’s emergent coordination between autonomous buildings, each optimizing for its occupants while sharing information with neighbors.

Takeaway

I don’t actually know if this technology will succeed. The researchers are upfront about the challenges, such as:

- Material durability

- Energy efficiency

- Scalability

- Cost

- Long-term maintenance

- Integration with existing building systems

- User acceptance over time, not just initial novelty.

But the point I’d like to make is, the philosophy is right, even if this particular implementation has hurdles to overcome.

The idea that architecture could be responsive & decentralized, that our buildings could learn from nature’s four billion years of evolution in self-organizing systems, that feels correct in some fundamental way.

We’ve been building static structures for millennia because that’s what our materials and technology allowed. But if we now have the ability to create dynamic environments that respond to changing conditions and human needs, why wouldn’t we?

The top-down approach has never worked for long. Environments change. People change.

But distributed systems where individual agents make local decisions based on local conditions while coordinating toward collective goals have been working for bees and ants for millions of years. That’s how ecosystems maintain stability while adapting to change. That’s how healthy human communities function at their best.

As I finish writing this, sitting in my very static, very non-responsive apartment, I can’t help but imagine what it would be like to wake up in a room that gently adjusts its light levels as the sun rises. That responds to the changing seasons. That blooms when I want it to and stays quiet when I don’t.

The future’s going to be strange, friends. But if we’re thoughtful about how we build it, if we learn from nature’s distributed systems rather than imposing rigid hierarchies, if we prioritize adaptation over perfection, if we give agency to individual elements while enabling collective intelligence, then maybe, just maybe, it might bloom beautifully.

And I’m here for it.

More information: Merihan Alhafnawi, Architectural swarms for responsive façades and creative expression, Science Robotics (2026). DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.ady7233